Chopin in Birkenau

Unforgettable and highly emotional experience for us was preparing and playing the melody of Chopin’s Tristesse (Étude Op. 10, No. 3 in E major) as arranged for voice and orchestra by Alma. We could not, of course perform that work publicly at any of Sunday concerts, because the playing of Chopin was forbidden under the Third Reich. We played it for ourselves and for women prisoners who snaked in to listen to something special, something that expressed through music our resistance to the German oppressors.

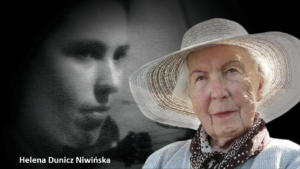

Helena Dunicz Niwińska, One of the Girls in the Band. The Memoirs of a Violinist from Birkenau, Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oswiecim 2014, p. 84

Fryderyk Chopin: Étude E-dur Op.10, No. 3

/”In mir klingt ein Lied”/

for voice and instrumental chamber ensemble

Instrumentation: Joanna Szymala

Lyrics: Alma Rosé

The Artists:

Flute: Alicja Molitorys Recorders: Karolina Jesionek, Julia Obrębowska Accordions: Marek Andrysek Mandolins: Wojciech Radziejewski, Sławomir Witkowski Guitar: Dawid Bonk Percussion/Cymbal: Wojciech Herzyk Violins: Krzysztof Lasoń, Shi Chen, Maciej Tomasiewicz, Monika Dziurawiec, Agnieszka Lasoń, Wojciech Klich, Agata Romejko, Piotr Wacławik Cello: Stanisław Lasoń Double bass: Łukasz Bebłot Soprano: Kasia Moś Conductor: Szymon Bywalec Recording Director: Beata Jankowska-Burzyńska Artistic Director: Katarzyna Naliwajek

This transcription is based on a pre-Second World War edition of In mir kling tein Lied, a song arranged for voice and piano by A. Melichar with lyrics by E. Marischka. © BEBOTON-VERLAG GMBH

A word on the origin of the recording:

Many German camps, Auschwitz included, had inmate orchestras. Their main duty was to play lively marches that accelerated the counting of the columns of inmates who left the camp to work in the morning, marching five abreast, and then also counting them in again on their return to the camp after their day of gruelling, strenuous work. There were 11 such orchestras in Auschwitz, one of them being the women’s orchestra set up in Birkenau in the first half of 1943. Operating initially under the baton of a Polish political prisoner, Zofia Czaykowska, the band presented a fairly inadequate level of musical performance. However, when a virtuoso violinist, Alma Rosé, became the conductor, the quality of their music gradually improved. This not only allowed a vast expansion of the repertoire beyond the marches presented de rigueur, but also the preparation and performance of concerts for the SS contingent and the fellow inmates. As the orchestra consisted of singers as well as instrumentalists, the conductor built up the repertoire and extended it to cover, in addition to contemporary hits, the fields of opera and operetta. Thus the band’s repertoire consisted of around 200 pieces on various subjects, most of them being the work of German composers. Working on individual pieces, Alma had to rework the parts of individual instruments to adjust them to the level of skill attainable by her players, and this often left plenty of room for improvement as she was dealing with amateurs. As the ambition and purpose of the conductor was to reach a satisfactory standard of playing, the pieces were sometimes practiced for ten hours a day and more. Besides the instrumentalists’ lack of skill, the range of instruments presented to the band was a challenge as only violins, mandolins, guitars, and flutes were available, therefore the obvious lack of a bass section was an especially severe limitation. Achieving a coherent sound with such a peculiar line-up required more than a musical talent: it called for plenty of hard work.

Early in 1944, when the Birkenau camp was inundated with the smoke belching out of the chimneys of the crematoria, and the inmates of the camp witnessed how the murder machine was gathering momentum, the score of Fryderyk Chopin’s Étude in E major, Op. 10, No. 3, also known under the title “Sadness” or “Tristesse”, made its way onto the sheet stands of the women’s orchestra. The piece was transcribed for voice and orchestra by Alma Rosé, who combined it with lyrics that she wrote. The music of Jewish and Polish composers, Chopin included, was forbidden, and both those performing and those listening to such music were given excruciating punishment. That is why the forbidden compositions were only played during informal musical events organised for a narrow circle of trusted listeners. Thus, all the women of the orchestra were aware that the piece would never be played in the official concerts. Indeed, the Étude was only played a few times in the orchestra barracks for the pleasure and satisfaction of the women working in the orchestra, who found it the only way of expressing their defiance of the situation in the camp. This musical “bolstering of the heart” was also witnessed by trusted fellow inmates from other barracks. Both they and the artists found listening to Chopin in the hell of Birkenau an important and unforgettable emotional experience.

The violinist Helena Dunicz-Niwińska believes this Étude of Chopin may be the only piece she played in Birkenau that could also resound today without sparking horrible memories of the camp, and yet it demonstrates the sound of the music that the women’s band played at the time.

This recording is an approximate reconstruction of a piece orchestrated at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp in 1944 by Alma Rosé and performed by her orchestra. The transcription of the Chopin piece was created on the initiative and with the help of Helena Dunicz Niwińska, a former violinist of the female camp orchestra, and with the help of her friend from the band, cellist Anita Lasker.

The recording was made in 2013 at the Academy of Music in Katowice. The piece was presented to the public for the first time during the official celebration of the 100th anniversary of Helena Dunicz Niwińska’s birth in Oświęcim in 2015.

In the photo above, in the center-Helena Dunicz Niwińska during the preview screening of Chopin in Birkenau. On the right, Maria Szewczyk – friend and co-editor of the memoirs of Helena Dunicz Niwińska One of the Girls in the Band. The Memoirs of a Violinist from Birkenau. On the left – Paweł Sawicki, who was in charge of the ceremony. One of the few drawings of the Birkenau women’s orchestra is visible on the screen: Mieczysław Kościelniak’s 1950 drawing “Return from Work” from the series Female Prisoner’s Day, from the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum Collections in Oświęcim.